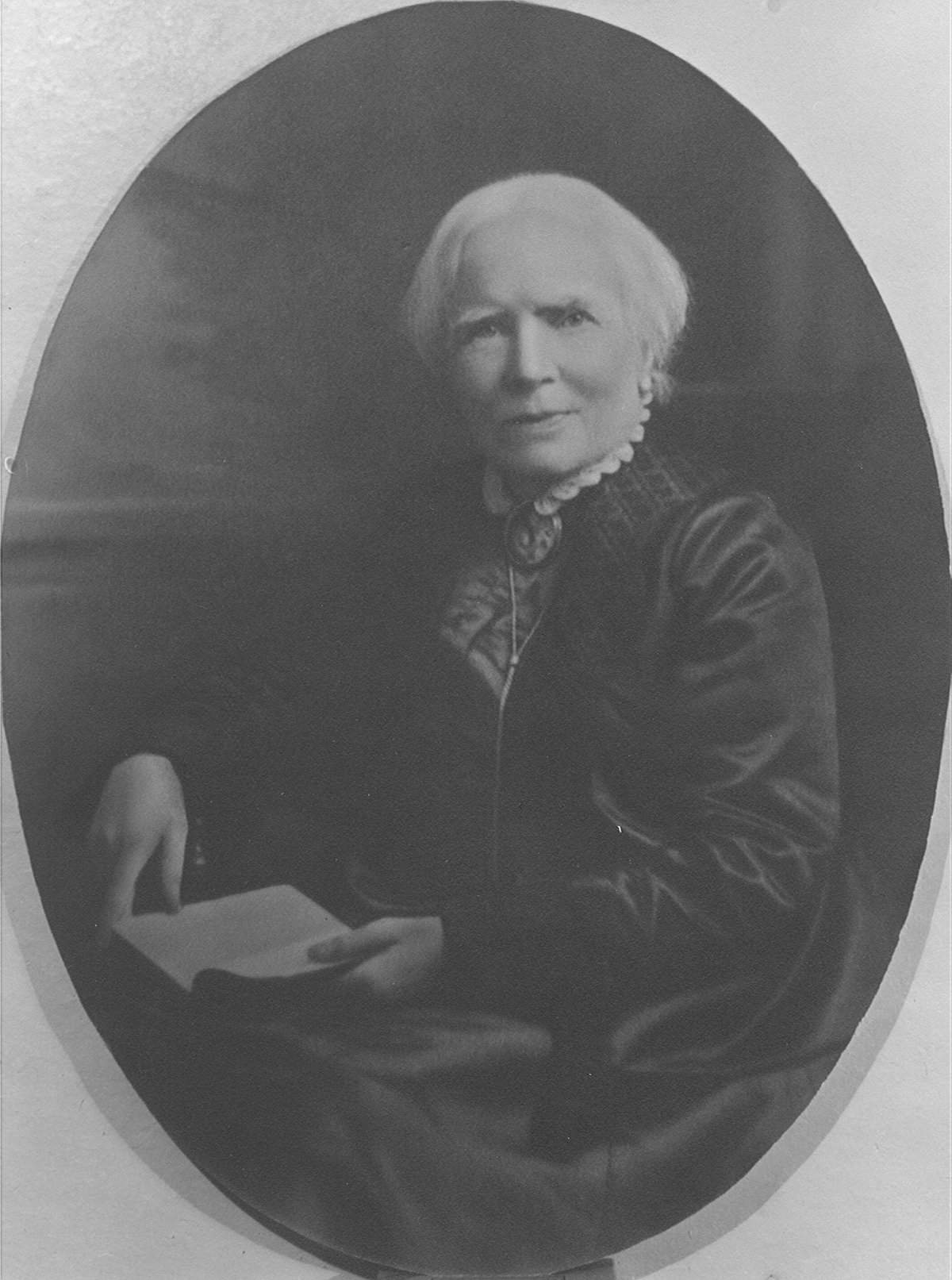

“Will you answer to the call, & let us sketch our future together?” Emily was six years younger, and her legacy has been obscured by her sister’s pioneering example, yet Nimura makes the case that it was Emily who truly loved the practice of medicine, and that her partnership was vital to their shared success. “Emily I claim you, to work in my reform,” Elizabeth wrote a few months before her graduation from medical school. More than anything, Elizabeth Blackwell became a doctor to show the world that she alone could do it. She denounced women as “petty, trifling, priest-ridden, gossiping, stupid, inane,” and desperately in need of leadership from a superior being like herself. And while she was roused by the Transcendentalist Margaret Fuller’s exhortation to “let them be sea-captains, if you will,” she was no feminist foremother: She did not believe in suffrage and rejected the fellowship of the burgeoning women’s movement. It was not a caring instinct that drove her - “I have no turn for benevolencies,” she wrote to her brother Henry in 1855 - or a curious one, to advance medical science beyond leeches, mercury and prayer. Nor is the answer easy to detect in her personality. No single story convincingly explains why a young woman “enthralled by literature and philosophy” should plummet into the earthy business of bodies. The most narratively appealing is 17-year-old Elizabeth’s experience caring for her father on his deathbed, in which “it is tempting to discern … the germ of her medical future.” Tempting, but too easy.

Nimura considers and discards a couple of possible origin stories. In her richly detailed and propulsive biography of Elizabeth and her sister Emily Blackwell, Janice P. At all levels of society, doctors had little more to rely on than “purgatives, laudanum and lancets.” What kind of woman would fight to join their ranks?

In wealthy homes, physicians coasted on charisma and connections as much as skill. Germ theory was more than a decade away, and in hospitals for the poor, surgeons in blood-caked aprons went from handling corpses to delivering babies without washing their hands. In 1849, when Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman doctor in America, the medical profession was neither well established nor well respected nor well paid. THE DOCTORS BLACKWELL How Two Pioneering Sisters Brought Medicine to Women and Women to Medicine By Janice P.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)